Even after all these years, the beginning of a new semester always smacks me upside the head a little more than I expect it will, and I've been away from blogging for a while, unless you count the rerun of a bit of social satire that I ran last week after the original post was quoted in a Chicago newspaper. I've been busy, though, what with teaching, getting the revised manuscript of Laureates and Heretics out the door, and writing an essay for Avant-Post, a book Louis Armand is editing for the very happenin' Litteraria Pragensia in Prague. I keep changing the name of the essay, but most versions include the phrase "Pastiche as Criticism," and today's re-entry into the inner blogosphere is fuelled by some of that project's fallout.

Even after all these years, the beginning of a new semester always smacks me upside the head a little more than I expect it will, and I've been away from blogging for a while, unless you count the rerun of a bit of social satire that I ran last week after the original post was quoted in a Chicago newspaper. I've been busy, though, what with teaching, getting the revised manuscript of Laureates and Heretics out the door, and writing an essay for Avant-Post, a book Louis Armand is editing for the very happenin' Litteraria Pragensia in Prague. I keep changing the name of the essay, but most versions include the phrase "Pastiche as Criticism," and today's re-entry into the inner blogosphere is fuelled by some of that project's fallout.

I've noticed several examples, lately, of critics straying into areas of composition where once only poets and fiction-writers dared to go. Specifically, I've noticed criticism being written in the form of pastiche, with the deliberate imitation, by the critic, of a pre-existing source text. This is interesting for all kinds of reasons, not least of which being the way it upsets one of our more established critical/theoretical applecarts: the idea that language is somehow entropic, that it becomes less meaningful the farther it moves from originality, and the closer it hews to the repetition (in style and in content) of earlier ways of talking. Here's Goethe taking this line, back at the end of the 18th century:

All dilettantes are plagiarizers. They sap the life out of and destroy all that is original and beautiful in language and in thought by repeating it, imitating it, and filling up their own void with it. Thus, more and more, language becomes filled up with pillaged phrases and forms that no longer say anything...

Okay. So Goethe tells us that we need linguistic innovation to regenerate cliched ways of writing, talking and thinking. We need heroic individual innovators to keep things fresh. If it all sounds a little avant-gardist, or at least modernist, it should (I actually came across the passage while reading a kickass essay by Jochen Schulte-Sasse, in which he claims that avant-garde ideas of lingusitic entropy and alienation are present much earlier than we tend to expect to find them, and are in fact coincident with the rise of capitalism). This is a way of thinking common to modernist writers (think Ezra Pound's "make it new"), and it persists today (think of Richard Rorty's riffs on Harold Bloom and the redescriptive power of the poet in the "Contingency of Selfhood" chapter of Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity).

But what if repeating, imitating, using pillaged phrases and the like becomes not the means of saying nothing but cliches, but rather the means of creating new insights? This was also a modernist idea, but it was a modernist idea in what we think of as the creative genres (poetry, the novel), not in what we think of as the critical genres (the lit-crit essay, say, or art history). (I know, I know, the dichotomy is false, but it persists in our usual modes of thinking -- bear with me).

This use of pastiche as a form of criticism seems to be the method of a few innovative critical types lately, including Benjamin Friedlander and my man David Kellogg. They deliberately take old bits of language and go about "repeating it, imitating it, and filling up their own void with it." The result isn't the banality Goethe feared, though, but the shaking-up of our received modes of critical thinking. Check it out!

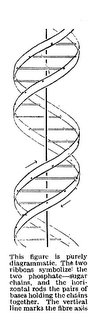

Here's Kellogg, who begins "The Self in the Poetic Field" with a pastiche made up of (in his words) "a line by line rewriting, with a few sentences removed, of J.D. Watson and F.H.C. Crick, 'A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid' published in the journal Nature in 1953.". The original essay, as every bio major knows, begins like this:

We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribose nucleic acid (D.N.A.).

This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest.A structure for nucleic acid has already been proposed by Pauling and Corey (1). They kindly made their manuscript available to us in advance of publication. Their model consists of three intertwined chains, with the phosphates near the fibre axis, and the bases on the outside. In our opinion, this structure is unsatisfactory for two reasons: (1) We believe that the material which gives the X-ray diagrams is the salt, not the free acid. Without the acidic hydrogen atoms it is not clear what forces would hold the structure together, especially as the negatively charged phosphates near the axis will repel each other. (2) Some of the van der Waals distances appear to be too small.

And here's Kellogg:

I wish to suggest a structure for contemporary American poetry (C.A.P.). This structure has novel features which are of considerable critical interest.

A structure for poetry has already been proposed by Eliot. He has kindly made his manuscript available to the world for the last eighty years. His model consists of an enveloping tradition, with the dead near the center, and the individual talent on the outside. In my opinion, this structure is unsatisfactory for two reasons: (1) I believe that the material that provides the poetic structure is the living community of readers, not the dead. Without the stack of coffins, it is not clear in Eliot's model what forces would hold the structure together, especially as the variously interpreted bodies near the center will repel each other. (2) The self of the poem is extinguished along with the poet.

Okay, that last sentence is a pretty big departure. But you get the idea. The original is inhabited the way a hermit crab inhabits another sea-critter's shell. Benjamin Friedlander takes this method to a whole new level in his new book Simulcast: Four Experiments in Criticism. Here's his description of the method of that book:

I describe these works as experiments because all four are based on source texts and thus inaugurate a species of criticism in which the findings only emerge after struggle with predetermined forms. Sometimes this struggle took shape as an exercize in translation, not unlike the re-creation of a sonnet's rhyme-scheme and meter. Often, translation was impossible, and the struggle resolved itself instead in an act of controlled imagination -- not unlike the sonnet's original creation. In each case, the production of my text had less in common with the ordinary practice of writing an essay than it did with the composition of metrical verse....[the book's] somewhat scandalous methodology [involves] the creation of criticism through the strict recreation of an earlier critic's text (or, more precisely, through as strict a re-creation as the discrepancy between my source text and chosen topic would allow). Thus, my "Short History of Language Poetry" follows the arguments (and even wording) of Jean Wahl's A Short History of Existentialism, while "The Literati of San Francisco" takes Edgar Allan Poe's Literati of New York City as its template.... Although I was predisposed in each of these pieces to certain arguments and conclusions, I willingly abandoned these when they became incompatible with the critical approach demanded by my source.

What's interesting to me about Kellogg and Friedlander are the ways they turn the dominant assumptions about language around. We do tend to think like Goethe: repetition of the past seems bad, derivative, weak, and destined to perpetuate cliches. But Kellogg and Friedlander avoid all this. In fact, their use of source-texts as a critical tool takes them away from their own instinctive thoughts about literature, and forces them into new insights, different from their own critical predispositions. This seems a lot like Oulipo to me -- the use of a deliberate, systematic form of writing, carried through with some rigor and against our 'natural' (that is, habitual) modes of composition and thinking, as a means of generating new insights.

What makes this particularly effective, I think, is the turning to source-texts at a bit of a remove from the dominant critical prose norms of our time. Kellogg leaves the humanities behind and seeks out a scientific source-text, while Friedlander turns to remote, belletristic stuff (Poe) or to a philosophy currently deeply out of fashion in the academy (Existentialism). This is different enough to break our usual norms of thinking, but familiar enough to generate insights that are still comprehensible, if not uncontroversial. It reminds me of a comment Vincent Sherry made about John Matthias' poetry and its use of arcane historical source-texts in Word Play Place: "on the one hand, the pedagogue offers from his word-hoard and reference trove the splendid alterity of unfamiliar speech; on the other, this is our familial tongue, our own language in its deeper memory and reference." We get an estrangement of thinking, but it is an estrangement based not on an absolute alienness, but on a revival and reexamination of disused discursive strategies.

The critics are doing it like the poets have been doing it for decades. This is positive, and I hope we can see more of it: nothing is more enervating than the prose-style of our immediate inheritance: the half-assed theoryspeak of the professoriate, 1979-1999. May it rest in peace. Long live pastiche as criticism!