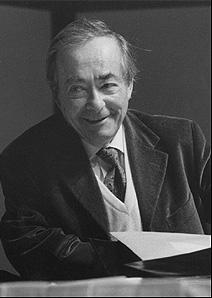

Here at last is the long-awaited blogging of the John Matthias retirement festival at Notre Dame some weeks ago. I was invited to speak on a panel and give a reading at what turned out to be a very well-attended event to mark the retirement not only of John Matthias, but of poet/fiction-writer Sonia Gernes as well. The day marks quite a changing of the guard at Notre Dame, where Cornelius Eady will be the new resident poet come the fall (along with John Wilkinson).

Coming in from Chicago on the South Shore railroad, I remembered three years of commuting in from my then-haunts in Wrigleyville/Boy's town. Back then I could count on a daily encounter with one or another version of derangement on the train: the guy who'd stand in the aisle and read from the Bible in Spanish, say, or the two south-side sisters who'd inevitably start arguing and, about every other week, break into a low-grade catfight, or the man who wore a pocket calculator like a badge on his jumpsuit, wrote mysterious numbers on a cash-register roll all the way from Gary to Michigan City, muttered about how he'd live in the woods "like an angel" if it wasn't for how strung out he was on "Juan Valdez Coffee." But no such luck: either the early morning trains have a different clientele from the later ones I used to take, or the city's sothward gentrification has increased social order at the expense of the ragtag alienation of old. The big industrial sprawl and decay was still there, though, through Hammond and Gary and the far south side. I'd forgotten how much those scenes had gotten to me, and how they'd found their way into a number of the poems I wrote for Home and Variations, a book I shamelessly flogged later that day, and which I'll shamelessly flog now: check it out here

The event turned out to the the best sort of literary gathering: an assembly of people who know about many things, care about the same things, and want to listen to each other. This is rare, really. Most gatherings fail either by lacking any focus, or by being too parochial. The big academic conferences (the MLA and its variants) are scattered and somewhat arbitrary -- who hasn't found themselves placed on a panel that should really have been called "Papers that We Couldn't Fit Anywhere Else"? They lack any real community feeling, and a shared professional affiliation can't quite make up for it. Too much gesselschaft and not enough gemeinschaft makes for a dull day. At the other end of the spectrum are those gatherings where the usual suspects get together to talk about the same short-list of poets. What can you say about these get-togethers?

All shuffle there; all cough in ink;

All wear the carpet with their shoes;

All think what tenured people think;

All know the text their neighbour knows.

Lord, what would they say

Did Frank O'Hara walk that way?

The best conferences I've attended have been things like Romana Huk's "Assembling Alternatives" conference on experimental poetry (almost a decade ago now), where everyone shared interests but where the parochialism was countered by a series of truly different perspectives (it was the first time I met Billy Mills and Trevor Joyce and Catherine Walsh and the other alternative Irish poetry crowd, and their take on Bernstein & Co. was new to me, and worth a hundred evenings spent listening to Ron Silliman's friends introduce one another at the group reading, hoping to have their membership in the tribe noticed and prominently blogged). Being there in Belgium when Maxine Chernoff, Paul Hoover, Joe Amato and Kass Fleisher got together with Antoine Caze and Michel Delville was just as good: everyone knew something different, everyone cared about some of the same things, and everyone cared a little differently. (Since I've just figured out how to make html links, I include a link to an account of that event: check it out here

The Matthias event was a best-case gathering: we all loved John's work, but we all knew it differently. Some of us were poets, some of us were critics, some were profs from other disciplines, some were artists, some were old friends of John's, some were relatives. Some highlights:

James Walton speaking about Matthias in terms of two types of egoism. While I've never thought of John as an egoist, Walton made an interesting case. The first kind of egoism, the bad kind, didn't apply to John, this being being the sort in which the egoist builds himself up by tearing others down. The second kind, though, was as John Matthias as any incantation of place names or any hiding of iambics in passages that pretend to be prose. The second kind of egoist enters a room and says to himself "this must be an interesting place, because I'm here!" You won't notice this egoist as an egoist, because you;ll be too busy basking in the Bloomsbury atmosphere he creates by his very presence. He enters a room, and suddenly everyone there feels that they're interesting, talented, clever, and on to something that really should be published right away. The second kind of egoist sees you as important, and wants to talk to you about the interesting thing you're doing. The second kind of egoist is the best of all possible mentors, since those around him bask in a glow of powerful approval (even your mistakes matter, though they need to be set right, since they represent a squandering of your very real, very important talent).

The second kind, though, was as John Matthias as any incantation of place names or any hiding of iambics in passages that pretend to be prose. The second kind of egoist enters a room and says to himself "this must be an interesting place, because I'm here!" You won't notice this egoist as an egoist, because you;ll be too busy basking in the Bloomsbury atmosphere he creates by his very presence. He enters a room, and suddenly everyone there feels that they're interesting, talented, clever, and on to something that really should be published right away. The second kind of egoist sees you as important, and wants to talk to you about the interesting thing you're doing. The second kind of egoist is the best of all possible mentors, since those around him bask in a glow of powerful approval (even your mistakes matter, though they need to be set right, since they represent a squandering of your very real, very important talent).

John kind of confirmed this later in the evening when he said that he'sspemt decades feeling like the youngest and the least intelligent person in the room, ever since his Deweyite highschool let him take classes at Ohio State. To hear that from one of the smartest people one knows, and from a man in the act of retiring from a long career is quite strange, and powerful evidence for Walton's position.

Walton, one of the most erudite people you're ever likely to run into, went on to talk of John's work as involving what Aquinas called magnanimity -- the spirit of doing things beyond the merely prudent. This, said Walton, was essential to art (although he told me later over a drink that he'd almost decided that it was ambivalence that was essential -- why make a work of art if you lack ambivalence, and can simply say what you mean?). The person who came on after Walton said something about agreeing with that, and about how poetry is always subversive. When I hear the words "poetry is subversive," I generally sigh or sneer. I mean, who do we in the little demimonde of poetry think we are? I almost choked on my chowder once when I heard someone at one of those U of Maine conferences say "the reason they're cutting funding for our magazine is that they know that in disrupting language we're disrupting power -- we're a threat." Disrupting the syntax on a page in a little magazine doesn't distrub your local arts council, let alone Dick Cheney. But what took place after this "poetry is subversive" comment changed my mind.

Here's what happened: the scene changed over from scheduled speakers to an open mike, and Jessica Maich took the stage. Jessica is a poet I knew in graduate school -- a good one, whom I hope will keep writing. She's also someone who has had a real life before graduate school (unlike me), raising a family in the midwestern community where she grew up. She came from a very different world than I did (I'm an academic brat, and my dad's an artist), so she saw the whole MFA world with different, and clearer, eyes than I did. "When I walked into that first seminar," she said at the microphone, "I thought, these people are arguing for forty minutes about where to place a comma. They're all adults, and this matters to them." This was subversive for her, and subversive in the way that Walton, thinking through Aquinas, would call magnanimous -- the actions that mattered exceeded the merely prudent. I think I was in that class, and for me at that point in my life there would have been no significance to an argument like that except as a drama in which the opinion of someone who was correct (me) and a bunch of misguided people who just didn't get it (anyone who disagreed with me) either triumphed or was thwarted (I was, as you may gather, something of a prick). But Jessica was starting to have a dialogical life in a way I hadn't, maybe haven't yet: she was seeing the logic of a world where conversations about comma placement were important, and the logic of that world was subversive of the logic of her other world, where practicality and prudence were more important than this kind of magnanimity. "They looked so normal," Jessica said of her poetry teachers John Matthias and Sonia Gernes, "they had houses and cars." But despite these signs of belonging to the world of the prudent and practical, they lived in another world, where serious adults cared for things like the comma in that stanza. So the comment about subversion meant a lot to her. Hey, I thought, wow, I get it. And I and felt like a bit of a twit for all of my internal eye-rolling at talk of subversion.

Other highlights for me include:

The Big Dinner, with hundreds in attendance. Nametag follies ensued, as Joe Doerr, Jere Odell and I handed out "Pope Pious II" and "Britney Spears" tags. I gave one labelled "eminence gris" to John Matthias, who was too graceful to take it off. My own read "Rufus T. Firefly," and I had a great moment when a group of grad student types were standing nearby and looking over at me and I overheard them talking about "whether that's him" and how "he looks like the picture on the book" but they concluded that I wasn't the poet in question because "he's Rufus someone or other." The award for best nametag goes to Joe Doerr, though, who went up to Steve Tomasula wearing a tag that read "Tom Stevasula."

Watching the big crowd in the LaFortune Center eating up Mary Hawley's poem about fourth-grade girl's basketball. The poem treats the moment of the first basket as a loss of innocence: suddenly the game mattered, and one could succeed or fail. The loss-of-innocence poem has been around forever, and yet, when one finds a convincing local habitation for it in experiences that one can render well, as Hawley did, people will always love it.

Discovering that Kevin Ducey looks a lot like Robert Duncan -- when he read his poems, all I could hear was "sometimes I am permitted to return to a meadow." Also laughing my ass off while having a smoke with Mark Mattson. Also drinking scotch with Dave Griffith, and hearing him tell me about his new book on the scandal of Abu Ghraib. Also meeting James Wilson or, as I call him, The Wintersian Kid, who read the manuscript of my book on the Stanford poets and liked it even though I'm no Wintersian. Also hearing Joe Frances Doerr talk about Ken Smith and David Jones, and then read his own poems, which sound a lot like Ken Smith-meets-David Jones. Also seeing poets Orlando Ricardo Menes and Francisco Aragon of the Latin American Studies institite -- especially since I ran into Aragon as he was buying a copy of my book (available online -- check it out here)

Many thanks to Coleen Hoover, who put the whole shindig together. Photos and (soon) transcripts are available at: this site.