From the deep, muggy swamps of Florida, from beneath the very shadow of Katherine Harris, and from the lingering pile of hanging chads and butterfly ballots, Mark Scroggins heroically blogs away about negative poetry reviews, among sundry other topics. Specifically, he notes my comment about the scarcity of negative reviews, a state clearly out of whack with the state of the art (we don't live in Lake Wobegon, so not all the books are above average). He notes my earlier comments on these things, but then rightly wonders if I'm not missing the elephant in the room:

I wonder if Bob ain't skirting the more proximate reason why there aren't more bad reviews of new books of poetry in the circles in which we travel: ie, because it's after all a pretty small world, the world of contemporary poetry that one cares about or theoretically ought to care about, & one's always chary of treading the toes of someone who might be willing to publish or review one's own work the next time around.

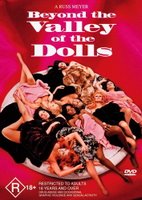

Too right! This is one more way that poetry reviewing is different from movie reviewing. I mean, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls aside, Roger Ebert doesn't harbor any ambitions to make another movie, so he doesn't worry about ticking off Clint Eastwood or Bruce Willis when he pans a movie. Not so in the deminmonde of poetry! Not in this our shadowy world of petty ambitions and resentments, where every reviewer has a manuscript of poems just waiting to be put into PDF format and sent off to press; where every journal editor has a similar manuscript; where half the publishers are in the same boat; and where the prize-givers are looking out for their pals. Ay yi yi. Someday American poetry's own low-rent version of L'Affair Jack Abramoff will come to light, I'm sure.

Too right! This is one more way that poetry reviewing is different from movie reviewing. I mean, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls aside, Roger Ebert doesn't harbor any ambitions to make another movie, so he doesn't worry about ticking off Clint Eastwood or Bruce Willis when he pans a movie. Not so in the deminmonde of poetry! Not in this our shadowy world of petty ambitions and resentments, where every reviewer has a manuscript of poems just waiting to be put into PDF format and sent off to press; where every journal editor has a similar manuscript; where half the publishers are in the same boat; and where the prize-givers are looking out for their pals. Ay yi yi. Someday American poetry's own low-rent version of L'Affair Jack Abramoff will come to light, I'm sure.

I mean, check out the gymnastics poor Mark Halliday has to go through in Pleiades when he wants to make some constructive criticisms of Helen Vendler's latest effusion of poetry criticism. Before he gets to his criticisms, he lists five reasons to praise Vendler, and then gets to that ever-present fear of those who write about big-wheels like Vendler: that the criticized bigwig will come down on the hapless reviewer hard, with the full weight of some kind of coked-up bionic sasquatch:

There is also a shady sixth reason to praise Vendler's book: she wields power in the contemporary poetry world; I might benefit from her goodwill, or suffer from her ill will! But of course it would be disrespectful both to myself and to Vendler if I were to let this worry skew my review.

Oh, Mark -- too late! I image you'll soon find yourself reduced to self-publishing on scraps of birch bark! And all that, just to say the truth: that the poetry world is too small and too incestuous for any kind of bad review to be safe. Except, of course, for the negative review of a book from The Other Tribe. You're safe if you've identified with one tribe of baboons and want to hurl feces at baboons from the neighboring tribe. (Was that my worst figure of speech yet? Surely I have sunk even lower...) I mean, you can sneer at the langpo guys if you're one of the new formalists, or dismiss as the product of the "School of Quietude" anything you don't like if you've signed up as one of Silliman's Mouseketeers (uh, I mean "as a practitioner of the Post-Avant"). So when we do get bad reviews, they're often more a matter of mutual antagonism than of careful and considered judgment.

What gets missed in all of the mutual back-scratching and inter-tribal chest-thumping is something we might call the "thumbs down because we care" review. Scroggins bemoans this situation, crying out from the kudzu-covered poetry yurt in his backyard:

I'm all for those careful, descriptive reviews of projects that one's largely sympathetic with; I'd like to see more critical, even cutting evaluations of worthwhile projects that one wishes succeeded but don't.

Oh, indeed. This is what we need. But the forces that condition our behavior mitigate against this sort of thing developing. That the material and social rewards for poetry remain pathetically low-stakes does little to change the situation. I suppose that's unsurprising to anyone who saw the fight over the preferable stapler in the movie Office Space, though. My guess is that the only solution to the problem is to not care about receiving the little rewards and perks of poetry, to let come what will, but not to jockey around trying to get an allegedly more prestigious job or a place in posterity. Easier to say than to do, but important, really.

**

In other news, Simon DeDeo has relocated to our fair city of Chicago. Already the weight of the hidebound eastern hierarchy falls away from his weary shoulders! Already he breathes the free midwestern air! Lo! See! Yea, he starteth a new journal.